Lulu Yang

“I must complete this; I aim to confront unease, confusion, and pain.”

Recycling Fashion: A Response to a Post-Pandemic World

What if discarded masks from a global crisis could be transformed into wearable art? Lulu Yang’s latest project, Bullet, Pellet, Tablet, does just that.

Unveiled at the BA Fashion Show 2024 at Central Saint Martins, the collection reimagines pandemic waste by using technology to recycle used masks into 3D-printed fashion. But for Yang, this project is more than sustainability and a fashion statement—it’s a deeply personal response to a post-pandemic world, reflecting on fear, resilience, and reinvention.

An interdisciplinary artist with a passion for theatre, fashion, film, and art, Yang takes a multi-layered approach to storytelling. This collection unfolds across a runway show, a live performance, and a fashion editorial, reinforcing her signature blend of innovation and social criticism.

Personal Background and Influences

Born and raised in southwestern China, Yang’s focus on working-class and social issues can be traced back to her upbringing in an industrial district. Her previous works have tackled challenging themes ranging from sex workers’ lives to county living conditions, from romantic illusions to identity crises. With Bullet, Pellet, and Tablet, Yang shifts her focus to a more immediate and universal concern, “affect”—the fear of danger, the sense of unease, and the intention to disguise or arm oneself in a post-pandemic, wartime world.

Initially questioning beauty standards in mass-produced fashion, Yang felt compelled to create something beyond mere visual aesthetic appeal. “I must complete this; I aim to confront unease, confusion, and pain,” she states. “On a macro level, this is a global crisis; on a micro level, it is my crisis of faith.”

Conceptual Framework: Colours, Politics, and Symbolism

The project’s title, Bullet, Pellet, Tablet, first emerged as a series of rhythmic words before revealing its deeper significance. Like a three-act structure in screenwriting, these elements respond to the sudden changes that occurred during COVID-19.

The bullet represents opposition to beauty—embodying restlessness, doubt, anxiety, resistance, and voice—designed as a reverse bullet that returns to its shooter. The tablet serves dual purposes: a metaphorical cure for chaos and disorder, while also acting as an archive of our times. The pellet grounds the concept in practicality, referring to the recycled mask materials central to the project.

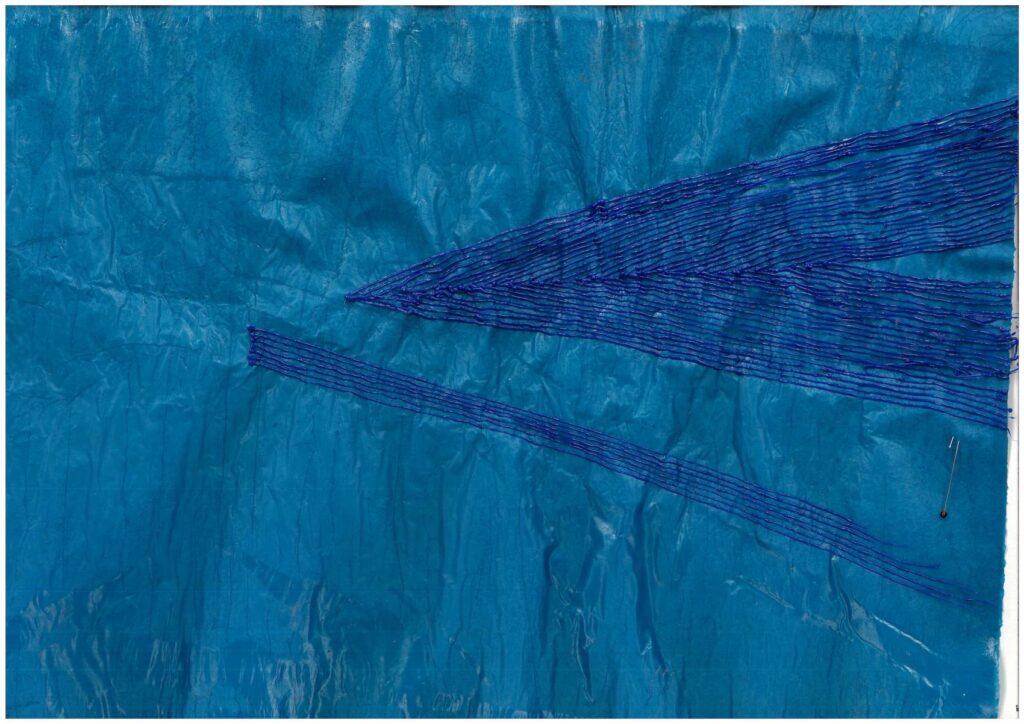

Additionally, colour plays a crucial role in Yang’s work, influenced by her personal experiences and cultural background. Yang shares her experience as a Chinese person with dyed red hair, who was directly associated with the communist symbol while travelling in Germany: “I found it fascinating that people could be so sensitive to colours, attaching so many meanings to them… So I also wanted to define colours (in my work), turning a calm blue into a kind of violent emotion as I define it.”

This exploration of colour’s political and emotional power draws inspiration from two key sources. The first is Chinese rock pioneer Cui Jian’s album Show You Colour, which uses red, yellow, and blue to express his attitudes toward social class and contemporary Chinese life.

Another inspiration is Political Pop and Cynical Realism, an artistic movement from late 1970s to early 1990s China, which employed bright colours and commercial symbols to convey humour and absurdity. These influences established colour as a fundamental language in Yang’s work, connecting politics, emotion, and artistic expression.

The Collection in Action: From Runway to Performance Art

Bullet, Pellet, Tablet first came to life at the CSM BA Fashion Show 2024, where the audience had the opportunity closely appreciate the complete six looks from the collection. The show opened with what would become the collection’s signature piece, almost completely made from 3D-printed materials: a model encased in a striking, Swiss Army knife-like blue armour, their entire body painted in the same intense blue shade.

As Cui Jian’s music filled the space, the dramatic entrance set the tone for what followed—three models wearing spiral headpieces in various colours, followed by two looks featuring covered faces, each reinforcing the collection’s central theme of disguise and protection.

The project took on a new dimension during a December 2024 group exhibition at The Good Rice Gallery. In this more intimate and provocative setting, Yang transformed the collection into immersive performance art. Wearing the iconic blue armour piece herself, the designer was joined by three nude performers whose bodies were painted entirely blue.

The performance began with Yang’s whistle, triggering the blue-painted performers to encircle her. Cladding in “armour,” which limited her vision, forced Yang to navigate the space through stretching out her hand and touch, creating a powerful metaphor for vulnerability and disorientation.

What unfolded was an exciting experience of tension and release. The performers’ sharp laughter cut through the space as Yang moved forward. The juxtaposition of cold blue bodies against futuristic PPE materials created an unsettling atmosphere, while the overcrowded venue amplified the sense of danger from the armour’s sharp elements. Audiences had to endure an unpredictable sense of oppression; an atmosphere of confusion and fear filled the dimly lit space.

As the performance progressed, the audience found themselves drawn into the spectacle. The exaggerated, explosive laughter of the performers invited audience participation, transforming their unease into nervous laughter from the crowd—a surreal celebration of madness and chaos.The result was a powerful commentary on our post-pandemic reality, where protection and isolation, safety and danger, and comfort and discomfort exist in perpetual dynamic tension.

Queering the Body: Beyond Gender and Form

The collection’s radical approach to body transformation found an unexpected catalyst in makeup artist Lil Soap, whose background in drag culture brought a fresh perspective to the project. Yang recalls the pivotal moment in their collaboration: “Previously, I would approach this project from a straightforward perspective, starting with making the clothes and then putting them on the models. At that point, I felt like my creative energy was exhausted. But then Lil Soap suggested painting the entire model blue. It’s a true sense of disguise. Because once you’re painted all blue, you can’t see anything, can you? I found it very interesting, and it gave me some new inspiration.”

While drag traditionally uses exaggerated makeup and styling to challenge gender norms, thereby emphasising the performative nature of gender, as Judith Butler argues, this project extends that concept beyond gender. By completely submerging the human form in blue paint, the work dissolves the boundary between body and environment, person and object.

The approach resonates strongly with posthumanist theory, particularly Donna Haraway’s conception that humans cannot exist independently or isolated; instead, we constantly interact with the world and the environment around us. By queering not just gender but the very notion of human form, the project suggests that our bodies are not merely vessels but sites of constant interaction with the world around us. The blue-painted performers become living sculptures, neither fully human nor fully objects, challenging viewers to reconsider their own relationship with the physical world.

Sustainability Challenges: Can Fashion Truly Be Eco-Friendly?

The staggering environmental impact of COVID-19 extends beyond public health—over four million tonnes of polypropylene (PPE) waste from discarded masks now threatens our ecosystems, causing severe and long-term ecological damage. For Yang, the ubiquitous blue medical masks became more than just protection; they emerged as “a symbol of this chaotic era. The environment is filled with this synthetic sky-blue shade—a form of blue hegemony,” she explains.

These masks, made from PPE, are difficult to recycle or dispose of in landfills. Confronting this crisis, Yang envisioned a radical solution: transforming discarded masks into materials suitable for 3D printing. However, the technical process became a major difficulty.

Single-use masks comprise multiple components—spunbond and meltblown nonwoven PPE, elastic straps, and aluminium nose clips—each requiring different handling. The recycling process presents multiple difficulties, as only the non-woven fabric portions can be recycled; the other components require manual disassembly. The recyclable fabric undergoes a complex process—washing, drying, shredding, and melting—before being mixed with colour masterbatch for 3D printing.

While sustainability remains a pressing concern in the fashion industry, achieving it proves complex and challenging. Yang acknowledges that the current technology is neither stable nor sustainable. High costs and immature machinery lead to flaws in 3D-printed products. The process requires further development to ensure true eco-friendliness and non-toxicity.

Nevertheless, the young designer maintains hope: “After the funding ran out, I couldn’t continue, but I hope to restart this project because I envision a day when discarded masks can be entirely consumed through this 3D printing technology.” Though the project’s sustainability goals remain a work in progress, its potential impact on sustainable fashion innovation is promising.

Looking Ahead: Where Do Bullet, Pellet, and Tablet Go Next?

Bullet, Pellet, and Tablet have successfully evolved beyond a traditional fashion collection, adapting to various forms of presentation that highlight both its visual and conceptual depth. The Good Rice Gallery performance was a pivotal moment, transforming the project into a multimedia dialogue. However, since it featured only one look from the collection, it felt like a fragmented extension rather than a full representation. Future iterations could place greater emphasis on showcasing the garments themselves, ensuring that fashion remains at the core of the storytelling.

Beyond its presentation, the project’s context is crucial to fully grasping its meaning. When audiences engage with the clothing, images, or performances on a purely visual level, some of the deeper themes—sustainability, resilience, and political undertones—may be lost. It would be exciting to see Yang’s continued exploration of how to integrate text with practice, which could enhance this dialogue, bridging the gap between aesthetics and intention.

In conclusion, through its blend of sustainable innovation, artistic expression, and social reflections, Bullet, Pellet, Tablet redefines fashion design. Yang’s work demonstrates how fashion can respond to global crises while pushing creative boundaries. By transforming waste into wearable art, the project does more than question the future of sustainable fashion; it urges us to reconsider what we discard, what we create, and ultimately, what we choose to become.

To see more of Lulu Yang’s work, visit her Instagram page here.